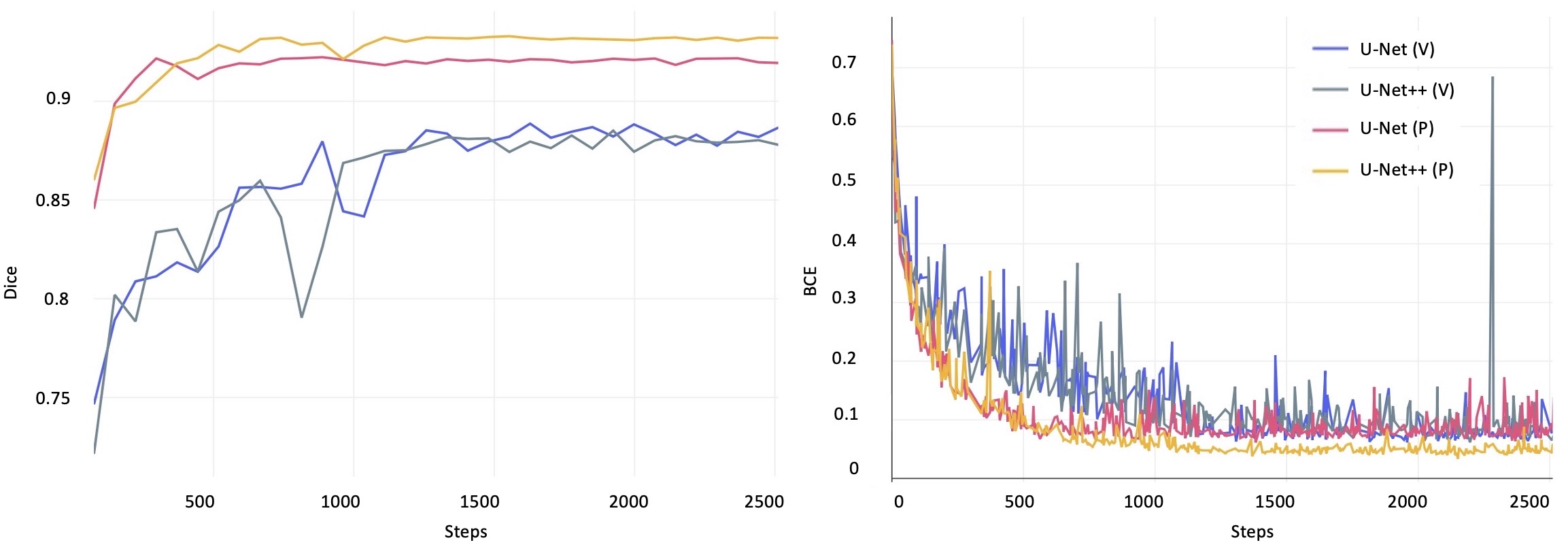

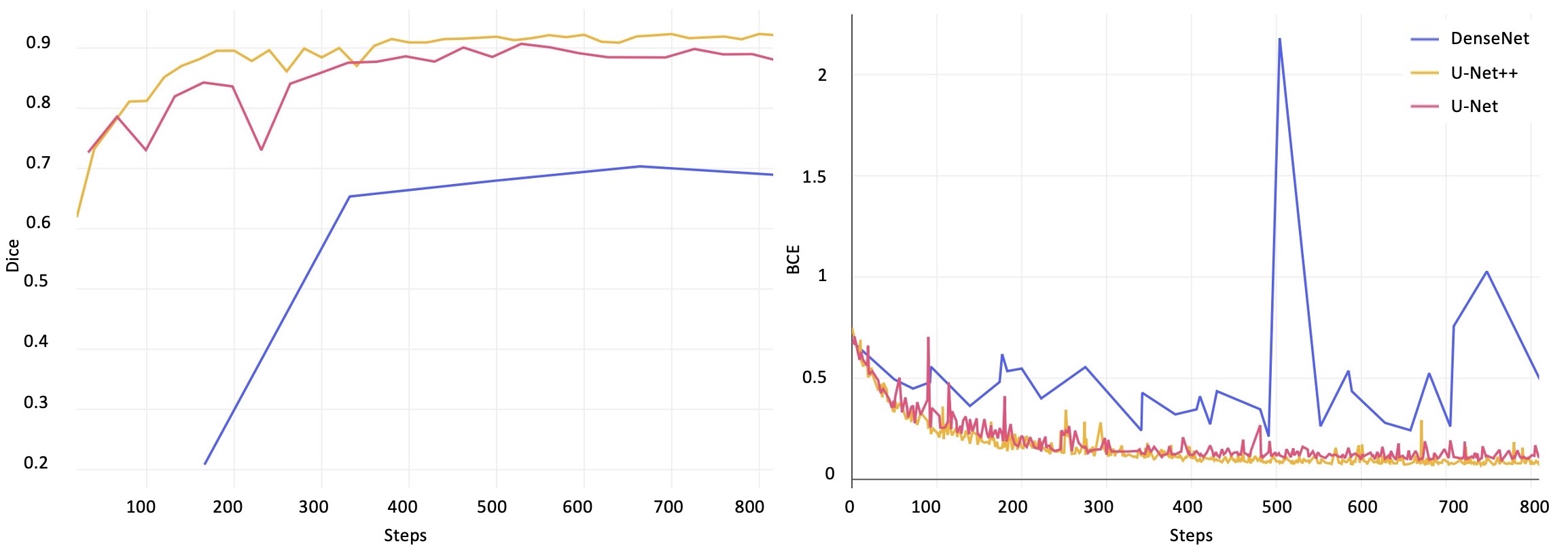

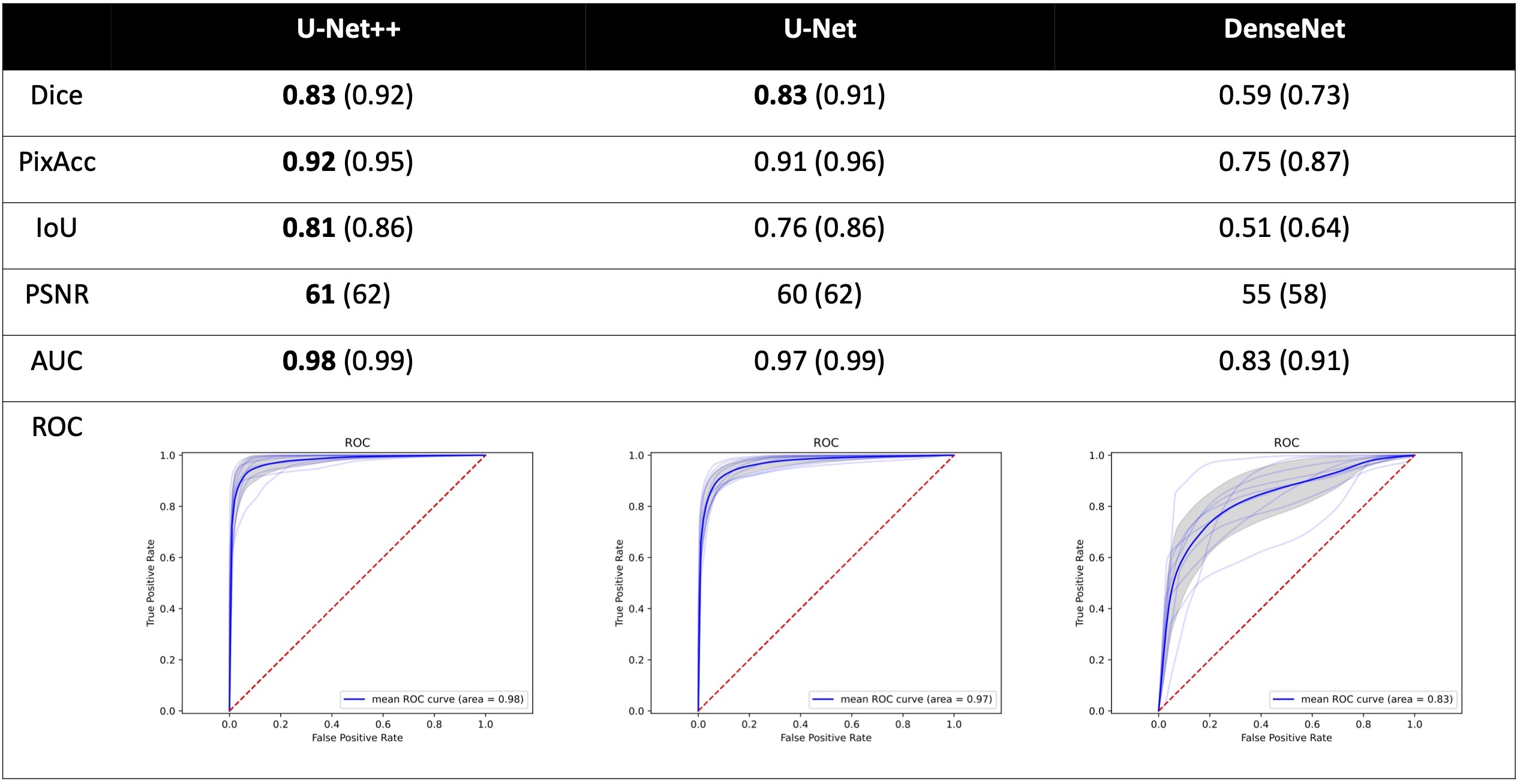

tl;dr StoneAnno is my first published first-authorship paper, presenting at SPIE 2022. My advisor, Prof. Ipek Oguz, connected me and my friend, David Lu, with Dr. Nick Kavoussi at VUMC who wanted to bring surgical endoscopy out of the dark ages. With the long-term goal of fully-automated robotic endoscopic surgery, we built a dataset of endoscopic kidney stone removal videos and investigated U-Net, U-Net++, and DenseNet for the segmentation task. We found a U-Net++ model that consistently achieves >0.9 Dice score, with low loss, and produces realistic, convincing segmentations. Moving forward, I am implementing our model on hardware for deployment in ORs, as a part of my master’s thesis, and I helped Dr. Kavoussi submit an R21 grant in October 2021. In the early stages of the project, we were also accepted for a poster presentation at the 2021 Engineering & Urology Society annual meeting.

Citation

Zachary A. Stoebner, Daiwei Lu, Seok Hee Hong, Nicholas L. Kavoussi, and Ipek Oguz “Segmentation of kidney stones in endoscopic video feeds”, Proc. SPIE 12032, Medical Imaging 2022: Image Processing, 120323G (4 April 2022); https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2613274

Abstract

Image segmentation has been increasingly applied in medical settings as recent developments have skyrocketed the potential applications of deep learning. Urology, specifically, is one field of medicine that is primed for the adoption of a real-time image segmentation system with the long-term aim of automating endoscopic stone treatment. In this project, we explored supervised deep learning models to annotate kidney stones in surgical endoscopic video feeds. In this paper, we describe how we built a dataset from the raw videos and how we developed a pipeline to automate as much of the process as possible. For the segmentation task, we adapted and analyzed three baseline deep learning models – U-Net, U-Net++, and DenseNet – to predict annotations on the frames of the endoscopic videos with the highest accuracy above 90%. To show clinical potential for real-time use, we also confirmed that our best trained model can accurately annotate new videos at 30 frames per second. Our results demonstrate that the proposed method justifies continued development and study of image segmentation to annotate ureteroscopic video feeds.

Results

Future

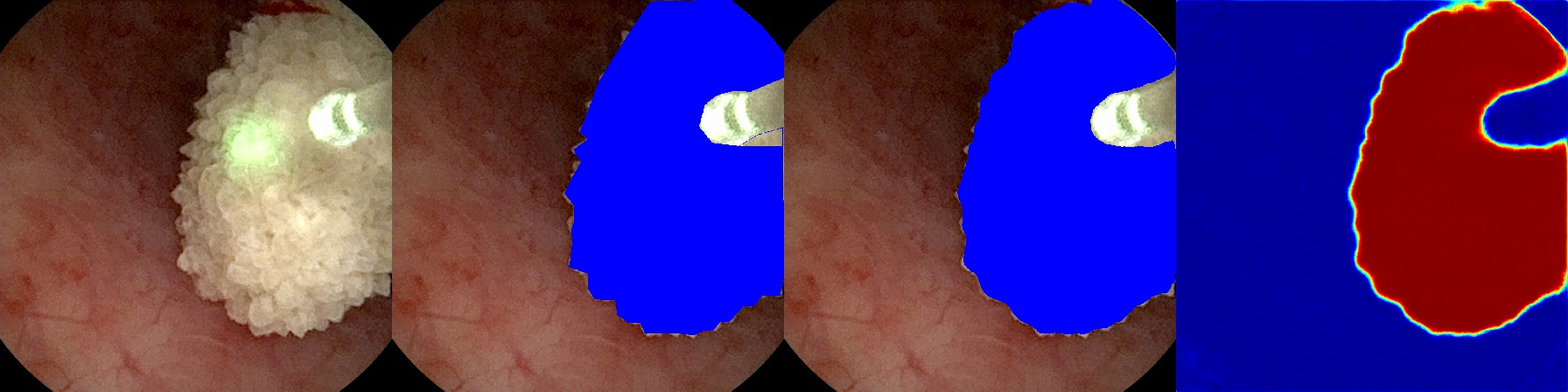

To deploy our high-performing model for surgical use in operating rooms, we will extend our video processing script to receive “in-step” frame-by-frame video input from a video capture card connected via DVI/HDMI to the endoscopic hardware. Then, we will output the side-by-side frames, as in Figure 5, to an adjacent monitor to assist physicians in surgery. Developing such a system will allow us to investigate further goals, such as monocular depth prediction which might prove critical in automation.18

We will also investigate the application of temporal models for our system. Incorporating information from previous frames might allow for more consistent prediction between subsequent frames. In addition, such models account for memory of data from previous frames without the overhead of additional input dimensions suffered by our current fully convolutional models. For this task, we will incorporate self-attention modules into our U-Net and U-Net++ architectures, which has been shown to increase performance in video segmentation.19

In practice, the problem domain also requires the segmentation of kidney stones after they have been surgically broken down into smaller pieces. The current dataset has been developed to support the segmentation of only whole kidney stones. Further development will include expansion of another section of the dataset where, as a surgeon breaks stones apart, the debris fragments will still be labeled by our model. In Figure 5, our model already segments clumps of debris; however, our future goal is finer granularity via an instance segmentation method.20

Additionally, we plan to incorporate multi-class segmentation to also identify, for example, healthy vs. un- healthy tissue. Since the task performs well on stone segmentation, we hypothesize that we can utilize the same underlying architectures to adapt to multi-class segmentation and that the model will perform similarly well, with relatively few manually annotated examples.21

References

[1] Minaee, S., Boykov, Y. Y., Porikli, F., Plaza, A. J., Kehtarnavaz, N., and Terzopoulos, D., “Image Seg- mentation Using Deep Learning: A Survey,” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelli- gence 8828(c), 1–20 (2021).

[2] Zaitoun, N. M. and Aqel, M. J., “Survey on Image Segmentation Techniques,” in [Procedia Computer Science], 65, 797–806, Elsevier (jan 2015).

[3] Badrinarayanan, V., Kendall, A., and Cipolla, R., “SegNet: A Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Ar- chitecture for Image Segmentation,” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 39, 2481–2495 (dec 2017).

[4] Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P., and Brox, T., “U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmen- tation,” in [Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics)], 9351, 234–241, Springer International Publishing, Cham (2015).

[5] Chen, L. C., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F., and Adam, H., “Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation,” (jun 2017).

[6] Simonyan, K. and Zisserman, A., “Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition,” in [3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015 - Conference Track Proceedings], International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR (sep 2015).

[7] Zhou, Z., Siddiquee, M. M. R., Tajbakhsh, N., Liang, J., Rahman Siddiquee, M. M., Tajbakhsh, N., and Liang, J., “UNet++: Redesigning Skip Connections to Exploit Multiscale Features in Image Segmentation,” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 39(6), 1856–1867 (2020).

[8] Safi, S., Thiessen, T., and Schmailzl, K. J., “Acceptance and Resistance of New Digital Technologies in Medicine: Qualitative Study,” JMIR Res Protoc 7, e11072 (Dec 2018).

[9] Nithya, A., Appathurai, A., Venkatadri, N., Ramji, D. R., and Anna Palagan, C., “Kidney disease detection and segmentation using artificial neural network and multi-kernel k-means clustering for ultrasound images,” Measurement: Journal of the International Measurement Confederation 149, 106952 (jan 2020).

[10] Viswanath, K. and Gunasundari, R., “Design and analysis performance of kidney stone detection from ultrasound image by level set segmentation and ANN classification,” in [2014 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI)], IEEE (sep 2014).

[11] Jegou, S., Drozdzal, M., Vazquez, D., Romero, A., and Bengio, Y., “The One Hundred Layers Tiramisu: Fully Convolutional DenseNets for Semantic Segmentation,” IEEE CVPR Workshops , 1175–1183 (2017).

[12] Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L., and Weinberger, K. Q., “Densely connected convolutional net- works,” IEEE CVPR 2017-Janua, 2261–2269 (2017).

[13] Otsu, N., “A Threshold Selection Method from Gray-level Histograms,” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics 9(1), 62–66 (1979).

[14] He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., and Sun, J., “Deep residual learning for image recognition,” IEEE CVPR 2016- Decem, 770–778 (2016).

[15] Sørensen, T., “A method of establishing groups of equal amplitude in plant sociology based on similar- ity of species and its application to analyses of the vegetation on danish commons”,” Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab 5(4), 1–34 (1948).

[16] Iremashvili, V., Li, S., Penniston, K. L., Best, S. L., Hedican, S. P., and Nakada, S. Y., “Role of Residual Fragments on the Risk of Repeat Surgery after Flexible Ureteroscopy and Laser Lithotripsy: Single Center Study,” J Urol 201, 358–363 (02 2019).

[17] Ward, T. M., Mascagni, P., Ban, Y., Rosman, G., Padoy, N., Meireles, O., and Hashimoto, D. A., “Computer vision in surgery,” Surgery 169(5), 1253–1256 (2021).

[18] Fu, H., Gong, M., Wang, C., Batmanghelich, K., and Tao, D., “Deep ordinal regression network for monoc- ular depth estimation,” in [Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition], 2002–2011 (2018).

[19] Ji, G.-P., Chou, Y.-C., Fan, D.-P., Chen, G., Fu, H., Jha, D., and Shao, L., “Progressively normalized self-attention network for video polyp segmentation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.08468 (2021).

[20] Zhou, Y., Onder, O. F., Dou, Q., Tsougenis, E., Chen, H., and Heng, P.-A., “Cia-net: Robust nuclei instance segmentation with contour-aware information aggregation,” in [International Conference on Information Processing in Medical Imaging], 682–693, Springer (2019).

[21] Kayalibay, B., Jensen, G., and van der Smagt, P., “Cnn-based segmentation of medical imaging data,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1701.03056 (2017).